6:00-8:00 pm ET | English, Spanish

NYU School of Law, Tishman Auditorium, 40 Washington Square South

Join Sarayaku, the NYU MOTH Program, Selvas Producciones, Local Contexts, Fungi Foundation, Cosmo Sheldrake, SPUN, and 070 for an exclusive screening of Allpa Ukundi, Ñukanchi Pura (Underground, Around, and Among Us), a powerful new documentary directed by Natalia Arenas, Diego Forero, and Eriberto Gualinga that traces a groundbreaking collaboration between the Sarayaku People of the Ecuadorian Amazon and a global alliance of scientists, artists, and advocates. The film captures the alliance’s efforts to advance Indigenous sovereignty and defend the Sarayaku peoples’ ancestral territory against extractive threats by documenting fungal and sonic life in the Amazon, all set against the backdrop of Sarayaku’s intrepid Kawsak Sacha proposal for life. Following the screening, participants can stay for a discussion with members of the collaboration to explore how science, sound, and sovereignty intersect in the fight to defend the Living Forest.

Panelists:

- José Gualinga

- Samai Gualinga

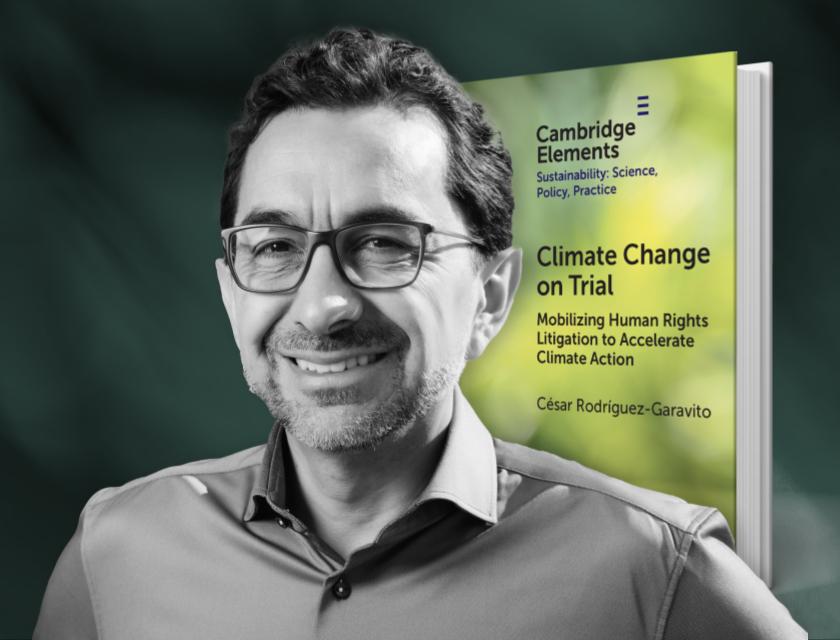

- César Rodríguez-Garavito

- Eriberto Gualinga

- Jane Anderson

- Adriana Corrales

- Carlos Andrés Baquero Díaz

This event is hosted by TAYJASARUTA (Kichwa Indigenous People of Sarayaku), Selvas Producciones, Local Contexts, Fungi Foundation, Cosmo Sheldrake, SPUN, 070, and the NYU MOTH Program at the Center for Human Right and Global Justice.