Research, litigation and broader advocacy on digital ID in countries like India and Kenya has already revealed the dangers of exclusion from digital ID for ethnic minority groups[1] and for people living in poverty.[2] However, a significant gap still exists between the magnitude of the human rights risks involved and the urgency of research and action on digital ID in many countries. Despite their active promotion and use by governments, international organizations and the private sector, in many cases we simply do not know how these digital ID systems lead to social exclusion and human rights violations, especially for the poorest and most marginalized.

Therefore, the Everyone Counts! initiative aims to engage in both research and action to address social exclusion and related human rights violations that are facilitated by government-sponsored digital ID systems.

Does the emperor have new clothes? The yawning evidence gap on digital ID

The common narrative behind the rush towards digital ID systems, especially in the Global South, is by now familiar: “As many as 1 billion people across the world do not have basic proof of identity, which is essential for protecting their rights and enabling access to services and opportunities.”[3] Digital ID is presented as a key solution to this problem, while simultaneously promising lower income countries the opportunity to “leapfrog” years of development via digital systems that assist in “improving governance and service delivery, increasing financial inclusion, reducing gender inequalities by empowering women and girls, and increasing access to health services and social safety nets for the poor.”[4]

This perspective, for which the World Bank and its Identification for Development (ID4D) Initiative have become the official “anchor” internationally, presents digital ID systems as a force for good. The Bank acknowledges that exclusionary issues may arise, but is confident that such issues may be overcome through good intentions and safeguards. Digging underneath the surface of these confident assertions, however, one finds that there appears to be remarkably little research into the overall impact of digital ID systems on social exclusion and a range of related human rights. For instance, after entering the digital ID space in 2014, publishing prolifically, and guiding billions of development dollars into furthering this agenda, the World Bank’s ID4D team concedes in its 2020 Annual Report that “given that this topic is relatively new to the development agenda, empirical research that rigorously evaluates the impact of ID systems on development outcomes and the effectiveness of strategies to mitigate risks has been limited.”[5] In other words, despite warning signs from several countries around the world, including chilling stories of people who have died because they were shut out of biometric ID systems,[6] the digital ID agenda moves full steam ahead without full understanding of its exclusionary potential.

Making sure that everyone truly counts

While the Everyone Counts! initiative only has a fraction of the resources of ID4D, we hope to inject some much needed reality into this discourse through our work. We will do this by undertaking–together with research partners in different countries–empirical human rights research that investigates how the introduction of a digital ID system leads to or exacerbates social exclusion. For example, we are currently undertaking a joint research project with Ugandan research partners focused on Uganda’s digital ID system, Ndaga Muntu, and its impact on poor women’s right to health, and older persons’ right to social assistance.

Our presence at a leading university and law school underlines our commitment to high quality and cutting-edge research, but we are not in the business of knowledge accumulation purely for its own sake. We will aim to transform our research into action. This could come in the form of strategic litigation and advocacy, such as the work by our partners described below, or in the form of network building and information sharing. For instance, together with co-sponsors like the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) and the Open Society Justice Initiative (OSJI), we are hosting a workshop series for African civil society organizations on digital ID and exclusion. The series creates a space where activists hoping to resist the exclusion associated with digital ID can come together, gain access to tools, information and networks, and form a community of practice that facilitates further activism.

Ensuring non-discriminatory access to vaccines: An early case study

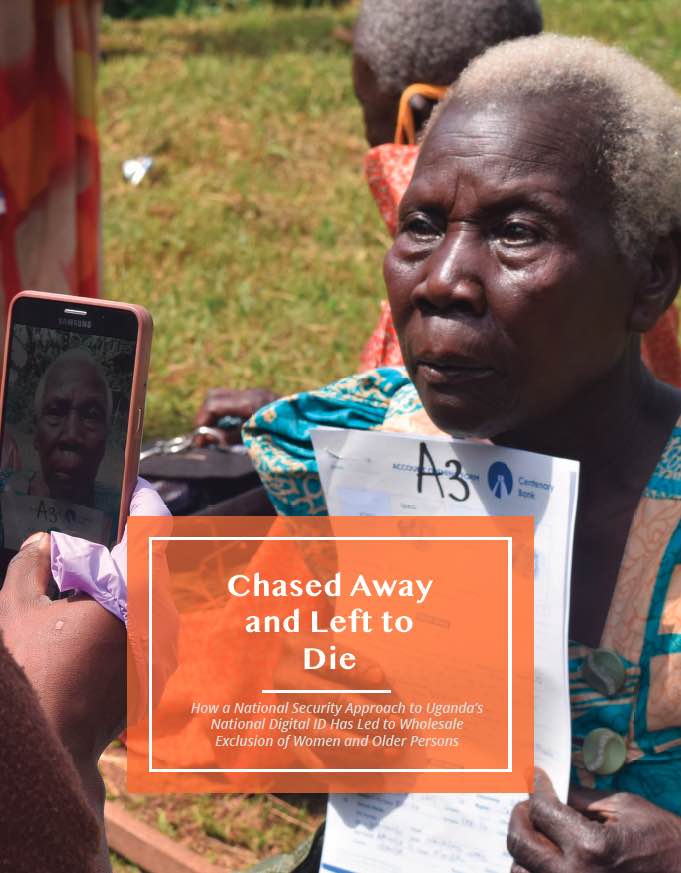

A recent example from Uganda demonstrates just how effective targeted action against digital ID systems can be. The government began rollout of its national digital ID system Ndaga Muntu as early as 2015, and it has gradually become a mandatory requirement to access a range of social services in Uganda.

To address the threat of COVID-19, the Ugandan government recently began a free, national vaccine program. One of the groups eligible to receive the vaccine would be all adults over the age of 50. On March 2, however, the Ugandan Minister of Health announced that only those Ugandan citizens who could produce a Ndaga Muntucard, or at least a national ID number (NIN), would be able to receive the vaccine. Conservative estimates suggest that over 7 million eligible Ugandans have not yet received their national ID card.

Our research partners, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), sued the Ugandan government on March 5 to challenge the mandatory requirement of the Ndaga Muntu.[7] They argued that not only would the requirement of the national ID in exclude millions of eligible older persons from receiving the vaccine, but also that it would set a dangerous precedent that would allow for further discrimination in other areas of social services.[8]

On March 9, the Ministry of Health announced that it would change the national ID requirement so that alternative forms of identification documents, which are much more accessible to poor Ugandans, could be used to access the COVID-19 vaccine.[9] This was a critical victory for the millions of Ugandans who seek access to the life-saving vaccine–but it is also a warning sign of the subtle and pernicious ways that the digital ID system may be used to exclude.

Humans first, not systems first

The Ugandan case study shows the urgent need for the human rights movement to engage in discussions about digital transformation so that fundamental rights are not lost in the rush to build a “modern, digital state.” In our work on this initiative, we will remain similarly committed to prioritizing how individual human beings are affected by digital ID systems. Listening to their stories, understanding the harms they experience, and channeling their anger and frustration to other, more privileged and powerful audiences, is our core purpose.

Digital transformation is a field prone to a utilitarian logic: “if 99% of the population is able to register for a digital ID system, we should celebrate it as a success.” Our qualitative work does not only challenge the supposed benefits for these 99%, but emphasizes that the remaining 1% equals a multitude of individual human beings who may be victimized. Our research so far has only confirmed our intuition that digital ID systems can deliver significant harms, particularly for those who are poorest, most vulnerable, and least powerful in society. These excluded voices deserve to be heard and to become a decisive factor in deciding the shape of our digital future.